Design

Ability and flexibility:

Designing technology for everyone

Last summer, in a dark auditorium somewhere around Minneapolis, EYEO hosted a series of lightning round presentations. Among the presenters that night was Claire Kearney-Volpe, a doctoral candidate and research fellow for the Ability Project at NYU. At the outset of her talk, she presented a simple form for the audience to fill out. That form had one not-so-subtle transformation: it was all set in Wingdings, a font designed as a series of glyphs that rendered the form incomprehensible.

Why Wingdings? Oftentimes, the simplest tasks – whether it’s entering a building or browsing the web – can be tedious, or even impossible, depending on where someone falls on the ability spectrum. Microsoft’s Inclusive Design Toolkit posits that, “If we use our own abilities as a baseline, we make things that are easy for some people to use, but difficult for everyone else.” Claire used Wingdings to transport a group of designers and coders to a world where they were no longer accommodated for.

I was floored. Her belief in a more purposeful and accessible web deeply aligns with Artefact’s values. To create a better future, it is the responsibility of designers to approach every project with the mindset of accommodating a wide range of ability. By doing so, technology is more usable for everyone.

I invited Claire to conduct a two-day, company-wide workshop at Artefact to help us further strengthen our skills around inclusive design – that is, design that is meant to be accessible to, and used by, as many people possible. I left with three key takeaways on how to approach accessibility and inclusion in my work.

1. Inclusive design makes better products for everyone

Disability is an inherent part of the human experience. There are more than 53 million people that live with some sort of disability in the United States. That’s roughly 1 in 10 people. Those numbers rise significantly, to about 1 in 5, when we factor in temporary, cognitive, or situational disabilities. Design has a major impact on how easily someone can interact with the tech products that our society is so reliant on. Designing inclusively doesn’t just affect those with disabilities, either. It broadens the reach of what we create from a product for many people, to a product for everyone.

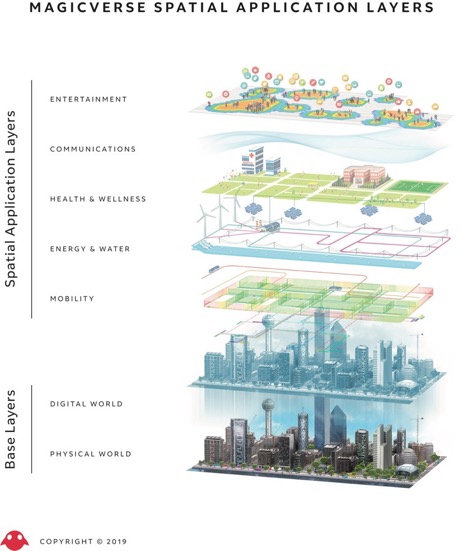

“It could be argued that everyone at some point in their lives will experience some form of disability – whether through injury, medical condition, or the natural aging process,” Claire says. “This is particularly important because technology is increasingly integrated into every form of our lives, from work and education to entertainment. It’s important we strive to ensure that people with a range of abilities can participate in these activities.”

This makes sense from both a business and ethical perspective. By explicitly providing a solution for someone who is hard of hearing, for example, the same design solution is also indirectly helping someone in a noisy bar. According to the World Wide Web Consortium for accessibility on the internet, there is a direct business case for inclusive design. “Businesses that integrate accessibility best practices are more likely to be innovative, inclusive enterprises that reach more people with positive brand messaging that meets emerging global legal requirements.”

The most interesting value, however, is societal. Designing inclusively creates a more equitable world, where everyone has equal access to products, opportunities, and experiences. There is far less opportunity for backlash, alienation and frustration. We no longer leave people behind.

2. Design for flexibility of use

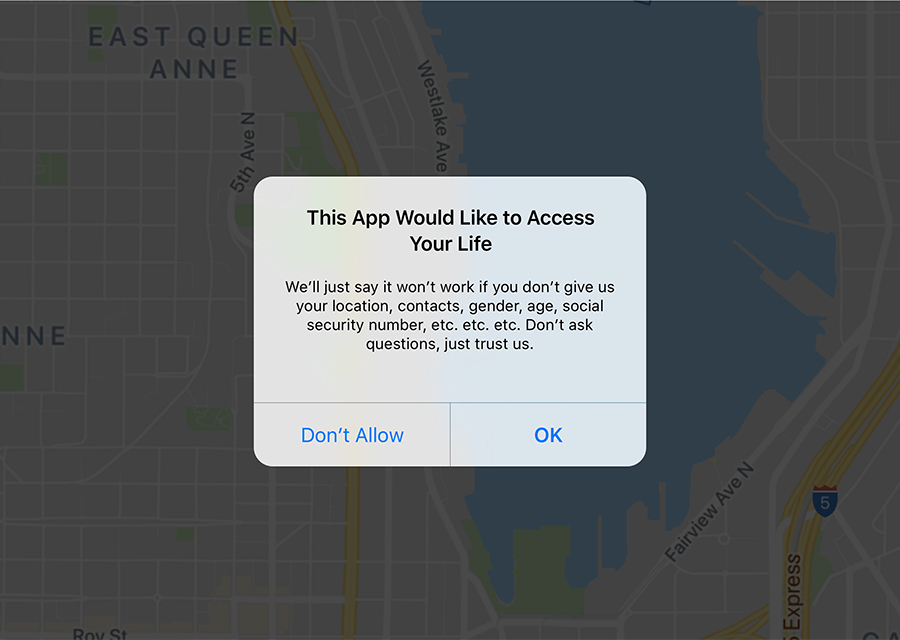

Designers tend to create tech products for a singular user experience. In other words, they are focused on a large group of people who have a similar range of ability. This approach has potential to mount measurable frustration by marginalizing all other ability groups. Addressing a narrow range of ability limits the equity that technology should provide. According to a Pew Research Poll, Americans with a disability are three times less likely to even go online. If design can be more inclusive, there is an opportunity to increase equity and access to the internet.

As the grasp of the experience age tightens its grip on our available senses, it is increasingly important to design systems that are as flexible as possible. In order to accommodate everyone, there should no longer be just one way to use products.

How can we improve the technology we create? There are varied industry perspectives on flexible design in practice. Claire suggests starting any project with the baseline question, “Is there only one way to interact with a system, or does it offer some flexibility of use?”

Ronald Mace, a pioneer in accessibility, led a group at North Carolina State University in creating the Universal Design movement. The movement and its principles aimed to facilitate the creation of singular, flexible design solutions to accommodate all users within a variety of spaces, from architecture to product design.

The common critique of Universal Design is that a singular design solution can’t accommodate the variance and range of ability. Designers should not expect that it is possible for a one-size-fits-all solution. “Inclusive design might not lead to universal designs,” according to designer Kat Holmes. “Universal designs might not involve the participation of excluded communities. Accessible solutions aren’t always designed to consider human diversity or emotional qualities like beauty or dignity. They simply need to provide access. Inclusive design, accessibility, and universal design are important for different reasons and have different strengths. Designers should be familiar with all three.”

3. Start early and POUR

To create products and experiences that are flexible, designers must address accessibility and inclusion head-on, from the start of a project. Often, designers view accessibility considerations as features and push them to later iterations in an effort to stand-up products quickly. That should not be the case. “[Accessibility] can’t be a pixie dust that you sprinkle on top of the program and suddenly make it accessible, which is the behavior pattern in the past,” quips Vince Cerf, a leading thinker in the accessibility space and known as one of the fathers of the internet.

As you begin the design process, it is important to note how people are using the existing systems that are in place. “We should not only focus on the accessibility of product consumption – consuming things in accessibility – but production or authorship too,” Claire points out.

The Designer’s Guide to Accessibility Research from Google provides an extensive methodology that is extremely helpful when beginning a new project. It includes tactics such as seeking out assistive technology to use when testing your design, and ensuring that you get perspectives from a wide swath of people who are in different places on the ability spectrum. This can help you better identify potential accessibility interventions and how they would improve your product’s flexibility and usability for a wider population.

When creating digital solutions, designers should adhere to the POUR methodology: that the experience is Perceivable, Operable, Usable, and Robust. POUR is a simplified approach to the extensive Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, the industry standard for evaluating the accessibility of digital products. Implementing the POUR principles helps designers create flexible interaction systems that accommodate a range of inputs and users; can better parse websites and operating systems; helps people contextualize and understand content in different ways; and predicts behavior based on patterns used in other places and on other devices.

WebAIM, a leading accessibility advocacy foundation based out of Utah State University, puts its best: “The POUR principles put people at the center of the process, which, in the end, is the whole reason for even discussing the issues [of accessibility].”

Inclusive design is human-centered design

Technology has helped people achieve more than we could have ever imagined, and it holds enormous promise to continue improving the human experience. Yet when we design technology for a limited range of ability, we leave many behind.

“Some of the things that are happening in [new technology] around accessibility is full of experimentation; it’s like the Wild West,” Claire told me. “I get excited, but I am grounded in the reality that there is a lot of room to improve with existing technologies.”

Our peers have built an extensive body of inclusive design research and methods to draw from. It’s now our responsibility as designers at the forefront of technology to approach our work as thoughtful advocates of inclusive design. We have the tools, conventions, and patterns to fix it. Let’s get started.