Perspectives

Why AI Needs UX

Just as the early days of Human Computer Interaction emphasized thoughtful UX to make personal computing accessible and intuitive, we now need the same intentionality in designing AI experiences.

AI model development and UX design must go hand in hand—because building powerful systems isn’t enough if people can’t understand, trust, or effectively use them.

Anyone who has conversed with ChatGPT or created an image with MidJourney might assume that a product leveraging generative AI doesn’t require much UX design—after all, these AI systems seem to understand us and follow our commands naturally. However, UX design remains just as crucial for AI-enabled products as it is for non-AI ones. A well-designed user experience ensures the AI product addresses real needs, instills trust, and enables intuitive and desirable interactions. Without thoughtful UX, even the most advanced AI can be misdirected, ineffective, or hard to use, preventing people from deriving real value. For companies developing these products, poor UX can be costly—or worse, harmful, as demonstrated by problematic AI systems seen in past incidences with self-driving cars, hiring, and mental health. Author Arvind Narayan of the book “AI Snake Oil” recently stated that:

“AI companies haven’t invested a lot of time into product development. They’ve made these models better but how to use that to improve your own workflows has been kind of largely up to the user. There needs to be a 50/50 split between model development and product development.”

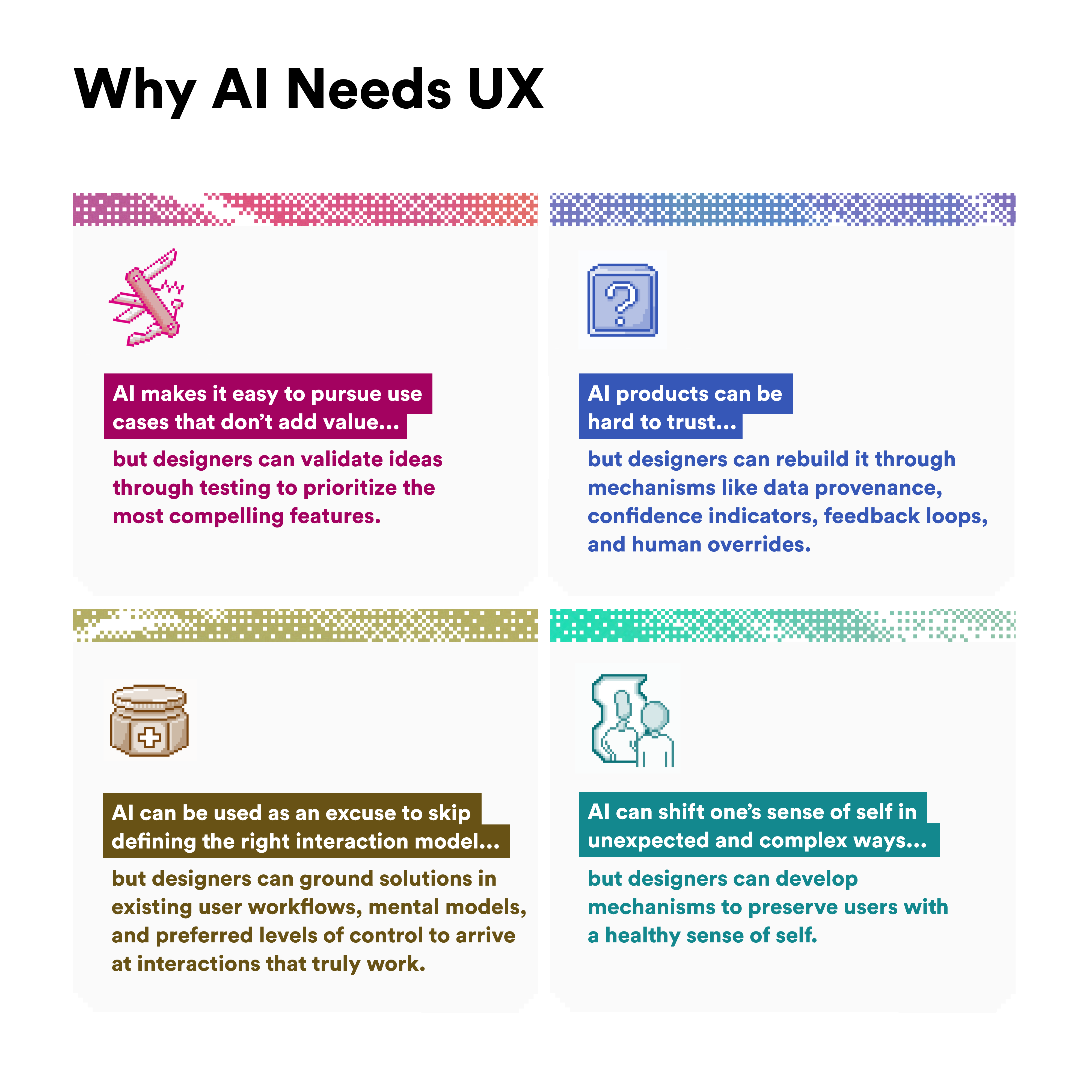

Here are four common pitfalls, or challenges, that innovators looking to leverage AI may encounter, and how UX design can help avoid them.

Challenge

AI makes it easy to pursue use cases that don’t add value, but designers can validate ideas through testing to prioritize the most compelling features.

Solution

Because generative AI is a powerful general-purpose technology, products built with it can serve a diverse range of use cases without much development time. Unlike other technological innovations like blockchain, which have relatively narrower applications, generative AI is highly adaptable—powering everything from creative content generation to automation, personalization, and decision-making. In this way, AI is like a swiss army knife, full of tools that can solve multiple problems. And with AI-driven companies attracting significant attention and funding, innovators can fall into the trap of building technology first and searching for a problem later. This approach can lead to products that are bloated with features that don’t solve real needs. Design helps innovators identify and validate various use cases by answering a crucial question: “Is this valuable?”

Consider the AI Pin by Humane. This product promises to serve multiple needs—acting as a virtual companion, introducing new music, and capturing spontaneous photos. It even transforms your palm into a display where you can view and control a timer with tap gestures. But are all these features truly desirable? What deserves priority?

Through research, prototyping, and user testing, UX design helps innovators identify the most compelling use cases and execute them exceptionally well. Without this focus, attempting to do too much at once can dilute the product’s effectiveness, resulting in a scattered experience, a muddled value proposition, and ultimately, a product that fails to resonate with users.

Challenge

AI can make products harder to trust, but designers can rebuild it through mechanisms like data provenance, confidence indicators, feedback loops, and human overrides.

Solution

Just as users need to trust products to use and adopt them, they must also trust the AI that powers those products. Rachel Botsman, author of “Who Can You Trust,” presents a framework describing four traits of trustworthiness that apply to people, companies, and technologies. Two traits relate to capabilities (competence and reliability)—the “how”, while two relate to intention (empathy and integrity)—the “why”.

We tend to trust others when they demonstrate two key qualities: competence—the ability to do what they promise effectively—and reliability—consistently delivering expected results. With humans, it’s relatively easy to assess these traits through conversation and interaction. But what happens when a system is 3x, or even 10x, more capable than any person we’ve encountered—and we have no real insight into how it works?

That’s the fundamental challenge with AI. As a black-box technology, its growing power makes it harder—not easier—to evaluate. While it’s relatively simple to notice improvements in AI-generated text, assessing the accuracy and reliability of AI-driven information or analysis—especially in unfamiliar domains—is much more difficult.

Here, UX design plays a role in helping make AI behavior more understandable, whether it’s recommending content, making predictions, or automating complex tasks. By designing for transparency, UX can foster trust through strategies like surfacing explanations for AI decisions (such as data provenance) and showing confidence indicators to help users gauge how certain the system is in its outputs. This is what Rachel Botsman terms “trust signals”—small, often unconscious clues we use to assess the trustworthiness of others or something. To see some of these ideas in action, check out our piece with Fastco.

Referencing Botsman’s framework again, UX design can also help Al-enabled products act with integrity (being fair and ethical) and with empathy (understanding and aligning with human interests and values). By incorporating diverse perspectives, needs, and values into the design process, UX helps create more inclusive and responsible AI systems. And frequent and extensive user testing enables designers to identify and address biases, unintended consequences, and potential harms before they impact users. This helps correct what AI field calls the alignment problem.

In addition, thoughtful interface design can provide clear affordances, feedback loops, and user controls. Examples include letting users know when its response is generally considered controversial by the public, having users rate an AI response to train it to be better over time (e.g., more personalized or accurate), and building in moments where humans can override the AI.

Challenge

AI can be used as an excuse to skip defining the right interaction model, but designers can ground solutions in existing user workflows, mental models, and preferred levels of control to arrive at interactions that truly work.

Solution

When we think of generative AI, we often default to imagining a chatbot. That’s no surprise—large language models are built to generate text, making chat a natural starting point. But simply slapping a chatbot onto an existing product rarely creates real value for users. It’s like applying tiger balm to every kind of pain—it might help sometimes, but it’s far from a universal cure. We saw this clearly with early banking chatbots; anyone who used them remembers how frustrating they were.

True innovation in AI-powered experiences requires more than just plugging in chat—it demands a deep understanding of existing workflows, user mental models, and interaction patterns. That’s where skilled UX designers shine. While text-based interfaces dominate today, the real future lies in well-crafted, multimodal experiences. For designers, this shift brings both exciting opportunities and complex challenges: choosing the right mode of interaction for the task at hand becomes more critical—and more nuanced—than ever.

For instance, natural language excels at complex queries like “Show me customers who spent less than $50 between 11am–2pm last month.” However, it falls short for spatial tasks—imagine trying to perfectly position an element through verbal commands: “Move it left… no, too far… right a bit…” These limitations become especially apparent in generative AI, where initial prompts like “Draw a kid in a sandbox” work well, but precise adjustments (“Make the sandbox 10% smaller”) become tedious.

For AI products to succeed, UX designers must determine the optimal level of user control over model inputs and queries, design clear ways for users to understand and modify AI-generated outputs, and create systems for users to effectively utilize those outputs. All of this must be wrapped in an interface that feels natural and easy to use.

Challenge

While great product design has always fostered emotional connection, AI-enabled products can introduce new psychological dynamics—such as discomfort and inadequacy, but designers can develop mechanisms to preserve users with a healthy sense of self.

Solution

Great products evoke emotions. From connected cars to smartwatches to payment apps, thoughtful design can surprise and delight users while making them feel understood and valued—creating a deeper emotional connection with both product and brand. AI-enabled products are no exception. Talkie and Character.ai are two bot creation platforms that successfully keep users engaged and interested. Similarly, Waze builds community through crowdsourced traffic updates and hazards and adds an element of play through customizable voice options and car icons.

What sets AI apart, however, is its seemingly superhuman capabilities, which fundamentally shift how people perceive themselves when using these technologies. It’s like a funhouse mirror that can perturb your sense of self. This phenomenon is explained in a HBR article titled “How AI affects our sense of self.” While productivity and creator apps can trigger job security concerns, using AI for writing essays or applying for a job often leaves users feeling like they’re “cheating” or inadequate. Companies must address these psychological barriers through strategic product design that acknowledges and accounts for these complex emotions. Again, UX design can play a role. To mitigate job displacement fears, design can emphasize human oversight, ensuring users remain central to meaningful tasks and decisions. To help users feel more comfortable with AI, products can incorporate teachable moments explaining why the AI is offering certain suggestions. This helps users enhance their skills rather than becoming overly dependent on AI.

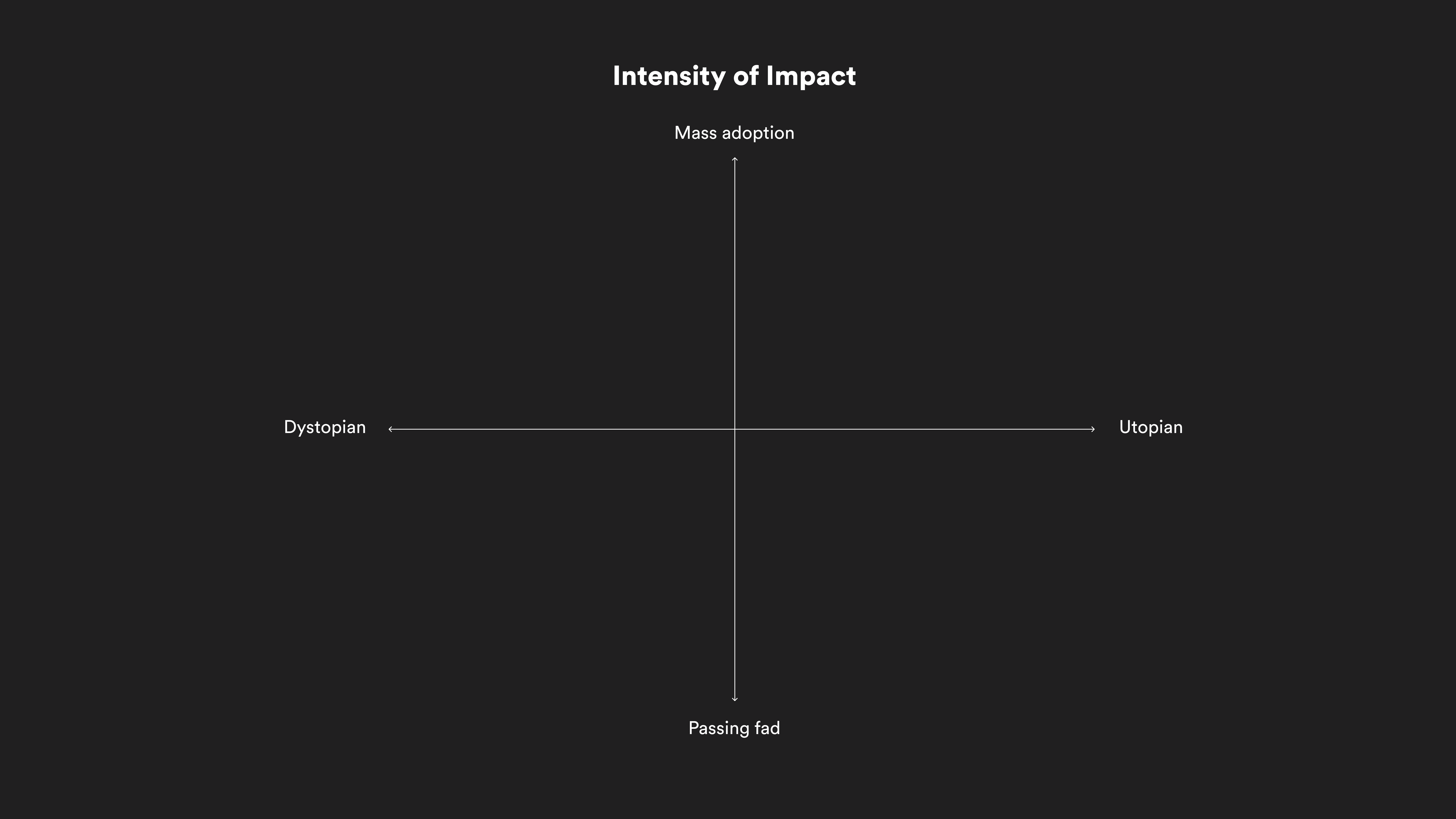

UX Design unlocks AI’s true potential for impact

While AI systems continue to advance at a remarkable pace, their success ultimately hinges on thoughtful UX design that puts human needs first. By focusing on generating real value, building trust, aligning with existing workflows, and considering emotional needs, designers can create AI-enabled products that are not just powerful, but truly impactful. The partnership between AI capability and human-centered design can deeply transform the human experience. Companies that bring design into their AI development, with intention and investment, will be the ones to create products that genuinely improve people’s lives.

Read Next: