Health

Diagnosing complexity:

A systemic look at treating rare conditions

I first learned about Bertrand in a New Yorker article. Born with a mysterious, debilitating condition, his case stumped the medical community for years. Misdiagnosis after misdiagnosis, Bertrand and his family lived in constant angst, uncertainty, and neglect in pursuit of a diagnosis. Underlying the human story, however, were conflicting incentives and repeated failures among the doctors, researchers and other stakeholders that comprised the patient experience.

Motivated by Bertrand’s story, we decided to explore the challenges affecting patients with rare and undiagnosed conditions through a systemic lens in order to better understand the wider system patients face; identify relevant stakeholders and their relationships; and pinpoint opportunities to improve research, treatment, and ultimately, patient health outcomes.

What makes the system so complex?

The healthcare system is ill-equipped to deal with non-traditional paths to diagnosis. Unlike a typical 43-minute episode of House, M.D., the majority of rare medical conditions take an average of five to seven years to accurately diagnose. This often means delayed treatment, severely compromised quality of life, and mounting financial burdens.

Doctors initially motivated to help diagnose and treat Bertrand’s condition would lose interest as soon as they determined that his ailment was outside the scope of their specialization, while researchers studying a particular medical condition were hesitant to work with other, potentially competitive, research groups.

“It was really frustrating for us,” Bertrand’s mother told the New Yorker. “Our child hot-potatoed back and forth, nothing getting done, nothing being found out, nobody even telling us what the next step should be.”

Patients and their primary caregivers cope with their conditions in isolation, and are expected to be their own researcher, advocate, fundraiser, and data scientist. This fragmented population inadvertently leaves patient data underutilized and reduces the incentive for institutions or private businesses to invest in rare disease research.

A lack of concerted efforts at scale to collect, manage, and analyze patient data, in turn, creates a barrier to diagnosis. This negative feedback loop reinforces the incentives and behavior that make diagnosing and treating rare diseases so complex and challenging.

In Bertrand’s case, it took four years to finally diagnose him with a rare genetic condition known as the NGLY1 deficiency. At the time of diagnosis, doctors believed he was the only known case in the world. As patient zero, Bertrand didn’t have clearance from the FDA to try experimental treatments, nor would any pharmaceutical company or research agency work on finding a cure. It was only after Bertrand’s father posted a blog searching for other patients that he was able to connect with several others suffering from the same condition and together create an advocacy organization.

Stakeholders have asymmetric influence

Complex problems often involve more than handful of stakeholders. As demonstrated in Bertrand’s story, the relationships and communication between dozens of individuals and organizations — from geneticists to health insurers — defined the discouraging patient experience.

To identify opportunities for design intervention in a complex system, we needed to understand stakeholder groups and their incentives in a more holistic manner. To do so, we created an Impact Continuum framework to assess stakeholders and their motivations, strengths, and weaknesses in a consistent manner. We generated profiles for the Impact Continuum by evaluating each stakeholder based on their power, expertise, interest and agility in the problem space.

Take Bertrand’s parents, for example. Despite being his primary caregivers, they initially lacked the ability to influence the system (power) or to self-diagnose (expertise). Yet their persistence in finding a diagnosis (interest) coupled with their resourcefulness and novel approaches — such as the viral blog post — demonstrate a high degree of nimbleness (agility).

Using the Impact Continuum above, we can begin to identify different opportunities for each stakeholder group. For example, how might we increase the sphere of influence for primary caregivers? How might we reduce the knowledge gap between primary caregivers and medical professionals? Taking it one step further, how might we augment the strengths of primary caregivers and mitigate their weaknesses through partnerships with other stakeholders?

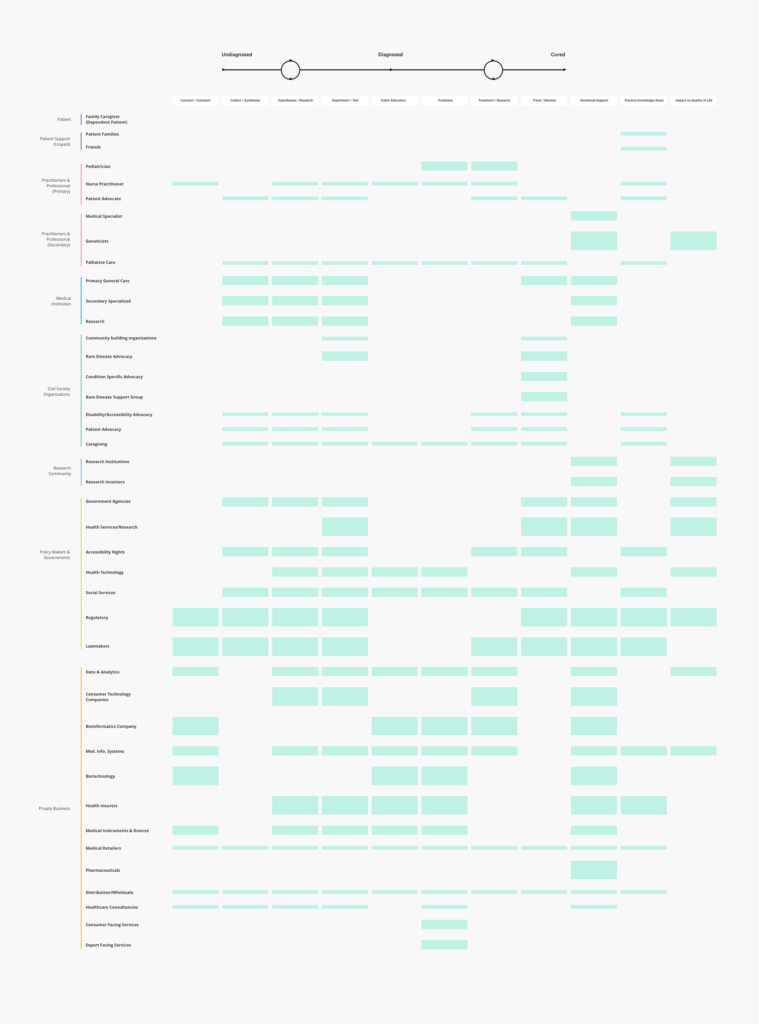

Opportunities for optimal impact

With a greater understanding of each stakeholder and their impact, we can investigate their roles within, and relationship to, the greater system. To do this, we mapped key steps on the patient journey from undiagnosed to cured, then denoted their level of participation and impact for each activity. This brings to light steps that are well-supported by influential stakeholders — as well as steps that lack support from those with high potential for impact — so we can narrow our focus for optimal impact.

The cross-pollination of stakeholder and steps on the patient journey allows us to not only ask which touchpoints reveal opportunities for intervention, but quickly identify the stakeholders that should be engaged to fill those gaps.

In Bertrand’s journey, the exercise helped to reveal a general lack of investment in collecting and synthesizing data for undiagnosed patients amongst high-impact stakeholders such as secondary care providers and bioinformatics companies. Leveraging this insight, we can then identify targeted opportunities for each high-impact stakeholder. For instance, how might secondary care providers better engage patients in collecting meaningful data for rare or unknown conditions? Similarly, how might bioinformatics companies support the data collection and synthesis needs of undiagnosed patients?

Where do we go from here?

Bertrand is now 10 years old. Although a cure has not yet been found, multiple therapeutic treatments are now available to him and patients with NGLY1 deficiency. Over the years, his parents worked with other families facing NGLY1 deficiency to encourage collaborative research and knowledge sharing, and even compelled the National Institutes of Health to begin studying the condition.

While a lot of positive progress has been made since Bertrand’s initial diagnosis, countless other patients facing rare and undiagnosed diseases continue to live through the same challenges every day. To imagine a future where patients like Bertrand don’t have to live their lives in perpetual uncertainty, we must think beyond products and technology and take a systemic approach to systemic problems. Only then can we design a future where patients facing rare or undiagnosed conditions can begin to find answers and a roadmap to healing.

As designers, we have the responsibility to challenge our own paradigms. Let’s forge new paths not just in pursuit of more innovative solutions, but of more thoughtful approaches to get there.